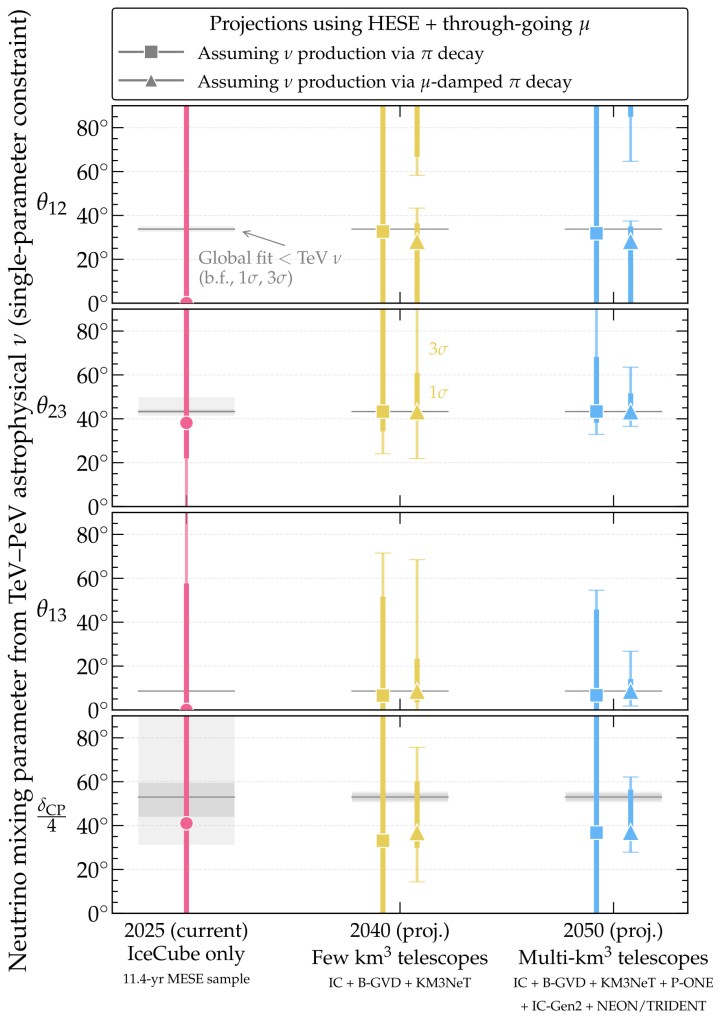

Today, the values of the neutrino mixing angles that govern flavor transitions are known to percent precision (the Dirac CP-violation phase is known much more poorly). However, these values are inferred exclusively from sub-TeV neutrino experiments. No measurement of the mixing parameters exists at the TeV scale and above. There, new-physics effects whose intensity grows with neutrino energy could modify the effective neutrino mixing. High-energy astrophysical neutrinos, with TeV-PeV energies, are primed for such measurements.

In a new paper with Qinrui Liu and Gabriela Barenboim, we have assessed in detail the power in these neutrinos to test mixing above 1 TeV, today and in the future. Concretely, we have extracted values of the four neutrino mixing angles (𝛉12, 𝛉23, 𝛉13) and the CP-violation phase (δCP) from the flavor composition of high-energy astrophysical neutrinos, i.e., the proportion of electron, muon, and tau neutrinos in their diffuse flux.

We extract present bounds on the mixing parameters from the 11.4-year IceCube Medium Energy Starting Events (MESE) sample, published in 2025. We find that the uncertainty in the measurement is too large to claim meaningful sensitivity to the mixing parameter.

For our projections, we use multi-neutrino-telescope combinations using projected detection rates at existing (IceCube, Baikal-GVD, KM3NeT) and future (P-ONE, IceCube-Gen2, NEON, TRIDENT, HUNT) neutrino telescopes. For these, we combine High Energy Starting Events (HESE) and through-going muons. Our projections show clear sensitivity to 𝛉23 and 𝛉13 (and, if neutrino production occurs via muon-damped pion decay, to δCP). This establishes benchmarks for the minimum size that new-physics modifications to the mixing parameters must have in order to be detectable.

Read more at:

Measuring neutrino mixing above 1 TeV with astrophysical neutrinos

Mauricio Bustamante, Qinrui Liu, Gabriela Barenboim

2602.14308 hep-ph